The conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine, even if they end soon, have set in motion dynamics from which there is no turning back. The EU and US must prepare for struggles extended in time and space. Beijing’s choices in the coming months will be crucial.

A view from China is important because the tensions around China are the fundamental backdrop within which both the Gaza conflict and the conflict in Ukraine play out.

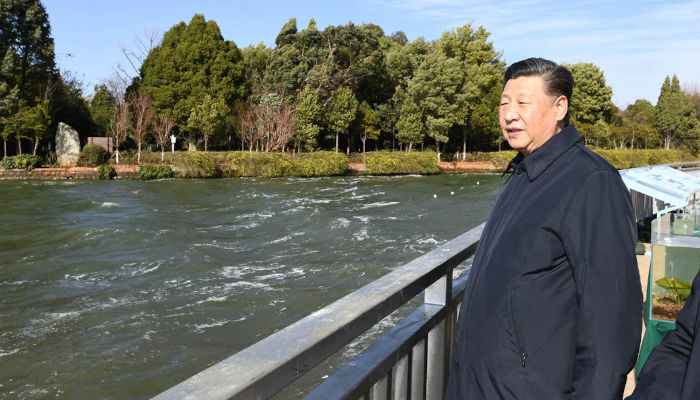

In November in San Francisco, with the meeting between US and Chinese presidents Joseph Biden and Xi Jinping, a kind of truce or cease-fire was signed between the United States and China over their tensions.

This assures the United States on the one hand that a third front will not open up anytime soon at least. To China, on the other hand, it allows a moment of pause because elections in Taiwan (a de facto independent island de jure part of one China) loom in January.

Here if the island declares formal independence and pushes the controversy against Beijing, the issue could become unsettling for Beijing. In addition, the economy is in serious trouble. Here China needs time and energy to get back on track.

The truce is good for both of us, but it is only a truce. We’ll have to see in the next few months, over a period of four to 14 months, whether this will provide room for something more substantial. Right now, it doesn’t.

And so, now backwards, you see what the horizons are. Of course, there is the Gaza conflict. Here it seems that Israel basically says that by March it will have taken over and eliminated the armed wing of Hamas.

That is a wish and a hope, because not only is Hamas Israel’s enemy but a coalition of enemies has formed against Hamas. There are the many Arab countries who do not want to be hijacked in their policies by Hamas after being hijacked by ISIS, al-Qaeda, and the PLO. And there is Europe, which, beyond the protests in the pro-Palestinian squares, fears the risk of a wave of Islamic terrorism sponsored by Hamas itself.

So, beyond the declarations of principle of this or that Middle Eastern government, in reality, there is a very broad consensus against Hamas.

There is, however, beyond that, a growing suspicion of Israel. It is a basic problem, because Israel since the 1993 Oslo agreement with the PLO has not made much progress in solving the Palestinian problem.

The Palestinian issue was put aside because it seemed unsolvable. So, if unsolvable, it was no longer an issue. It was a position, while understandable, that has exploded in recent months. The future is still that the Palestinian issue has to be resolved one way or another, because millions of people need a credible idea of a future that is not just the alternative between staying in a closed space or surrendering to Hamas terrorists.

Israel has to think about another perspective. Now perhaps it is emerging. It has opened up the idea of the Cotton Road: a political/commercial communication route that goes from India through Saudi Arabia, then Jordan and Israel, and then into Europe.

Israel has to find a way to integrate more and better with the rest of the Middle East. Israel has to stop being a kind of European outpost in the Middle East. It has to be a bridge to Europe and the West in the Middle East. It has to be a space of growth for Israel itself, for the Middle East, and for the whole West.

This means changing its relations with friendly but also unfriendly countries. The sort of armed peace that has been held for years with Syria or with Iran needs a stabler solution not only from Israel but perhaps also with the participation of other countries in the region.

Ukraine

Then, the end of the Gaza conflict of course will reopen world attention to the conflict in Ukraine, which is now in a tough spot. Russia is struggling. Ukraine is struggling. It is to be seen whether, in three to four months, as spring arrives, there will be glimmers of a true truce between the two sides, or a victory by either side. For now, a collapse of the total Ukrainian front within these three to four months seems unlikely, although in theory it is possible.

After the Gaza war ends there will be more world attention, and more world commitment to resolving the Ukrainian issue, because the war in Ukraine cannot be allowed to worsen year after year. It is a loose cannon kindling other conflicts, if it doesn’t end soon. Then a resolution is in everybody’s interest.

Here, just as Hamas’ solution in Gaza opens unfinished business with Syria or Iran, an eventual end (of any kind) to the war in Ukraine opens the question of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Kyiv’s critics argue that at the end of hostilities Ukraine will become some kind of a political black hole, a country in total disarray. Therefore Kyiv and its backers will have lost the war.

The real point, however, is that two years ago Ukraine did hardly exist politically. It had no army, almost no soldiers, no tanks, artillery, or air force. Will it be defeated on the ground today? Maybe yes, maybe no. But that the Russian superpower after two years cannot break through in a traditional war (not Afghan guerrilla warfare) and had to resort to help from China, Iran, and North Korea is an unparalleled failure.

It is possible that, whatever the outcome on the battlefield, many political balances in Moscow could blow up when the guns have stopped firing. Also, now it looks like Russia is getting the upper hand but that coincides with the Western distraction over Gaza. Then, is Hamas saving Putin? These are guerrilla tactics (or fortunes), asymmetrical warfare stuff, not demonstrations of traditional power.

One could go on and on counting the thousand holes in Russia’s troubles.

There is concern that Russia will collapse, as happened with the tsars’ regime or the Soviet regime, which would create a huge geopolitical vacuum. If Ukraine alone collapsed, it would be more manageable. However, such has been Russian fatigue that even a Ukrainian collapse would not safely prevent a Russian collapse or domestic political earthquake. And it is possible that Ukraine would not collapse. In the 1950s the U.S. supported a Ukrainian guerrilla war but abandoned it after a couple of years. The Ukrainians went on for a decade against the Soviets without any support.

Today they stood their ground and repelled the Russians for two years. It seems unlikely they will surrender tomorrow. Moreover, there is the case of the Prigozhin’s uprising (the head of the Wagner group who marched on Moscow) in June. It does not seem to be an isolated incident but a symptom of deep tremors in Moscow. Kyiv is also shaking but there are many external political forces that can hold Kyiv together. Moscow has to go it alone. I don’t think Beijing, Tehran, or Pyongyang are players in the Kremlin’s plots.

Then, Putin or Moscow really needs a lot of imagination to get out of this swamp. As of today, the most likely outcome appears to be a stalemate. But even if both sides accept a stalemate, it may save Russia from implosion, but not Putin from an internal showdown.

In March

It remains questionable that the Ukrainian issue will be resolved by March. Moreover, even if it were, it would open up political consequences in Moscow. Even the theoretical possibility of it happening is destabilizing. That is, Putin has no interest in ending the war. A “victory” of his own to sell convincingly to his acolytes is very difficult if not impossible. Putin, for his survival, needs the continuation even at low intensity of the war, which will keep him in power and perhaps consume his internal or external enemies by slow fire. Or he needs to cut some kind of a deal with the Americans, something that could leave China more isolated.

On the other hand, the end of the conflict in Gaza opens new fronts of at least political attention in Lebanon, Syria, and Iran.

That is, there is a prolonged horizon of a piecemeal world war, as the Pope described the present situation, that extends in time and widens in space. There is no longer a return to the peace of before the war in Ukraine. There is a low- or high-intensity war that hopefully can be limited in time, space, and violence but with which the whole world, starting with Europe, must understand it must live with. This means that Europe, and also the U.S., must wake up from the dream that peace will soon return, and must gear up for a protracted conflict to hopefully be contained. Unless a dramatic change for the better takes place soon.

This underscores how critical the upcoming U.S. elections are. We don’t know who the new president will be: Whether Biden will be confirmed, or Donald Trump will return, or there will be a third candidate who will prevail over both.

In a state of enormous uncertainty, perhaps unprecedented in the United States, with deep rifts in American society, politics, and culture, these elections could be vital.

It all takes place without a space for international settlement. The UN can no longer be a real place of mediation. This is probably due to the fact that at the end of the Cold War, when it was still an instrument designed for the Cold War, the UN should have been transformed. It has not been, there has been no reform of the permanent Security Council.

Today, the organization is hostage to numbers, to smaller/developing countries that sometimes sell out to this or that interlocutor for pennies. There is a problem with the UN’s true representation. It certainly does not represent advanced countries, it does not represent perhaps developing countries, and it is an empty institution.

Finally, there is anti-Semitism, an issue that directly affects Christians and Muslims, the majority of the planet’s population.

For decades it was taken for granted that the anti-Semitic/anti-Jewish issue had been settled and few had doubts about it. The horror of the Shoah was supposed to be enough to vaccinate everyone against future anti-Jewish regurgitations.

The protests of these days, which do not tell apart the massacres of Hamas and the more or less questionable policies of Israel, bring to light the infernal seed of anti-Semitism.

Those concerned about anti-Semitism must address the problem and not simply in defense of Israel or defense of Judaism, but in the name of tolerance and liberal society. Because if you kill and cripple freedom in democratic societies, it brings back anti-Semitism and then other intolerances come in its wake.

It is a battle of liberal culture against the regurgitations of authoritarianism and tyranny coming from so many parts of the world.

In other words, China has a horizon of four to 14 months, from the end of the Gaza war to the inauguration of the new U.S. president, to figure out how it will play and what it will do in the future. China’s position in turn will affect the war in Ukraine and the Middle East or new tensions from other parts of the world.