Looking at it from the outside, it is like a contest of bodies and minds.

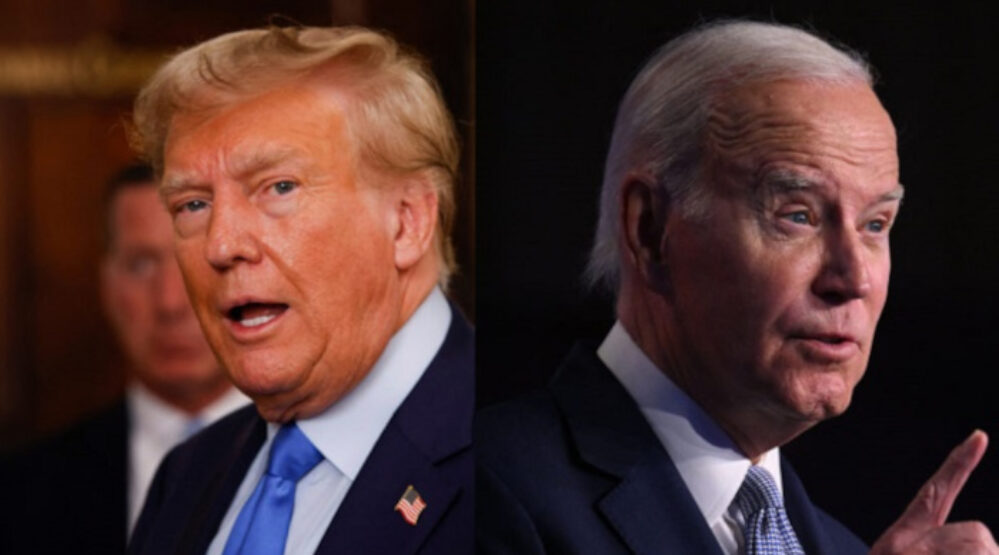

Donald Trump is big, has dyed, fake hair, and his statements are often prejudiced according to some present sensitivities and always glib. He seems to want to cheat age and reality, trying to look young and cocksure. He harks back to a past and a fantasy where strong and slick was beautiful and quintessentially American. In this framework, Trump makes sense. He legitimizes and gives dignity to those who feel left behind by the ongoing evolution of the United States.

His followers find a common ground that they have lost. They seem to resent a world where everything is complicated, where the U.S. needs to discuss everything with allies and partners, each with a different idea. They want to go back to a world where the U.S. was the only one that counted; it could decide by itself or just by consulting with a junior partner, the U.K. His statements, “lies,” defy verification because they almost belong to the alternate, dystopian world that refuses the present one.

Joseph Biden is the opposite. His hair is white, he is thin, his step is at times unsteady, and at times he looks frail. His 81 years are all there for everyone to see. He doesn’t want to cheat about being elderly; he shows it with pride. His answers sometimes are out of sync, but other times, they are mighty and powerful, showing the once-coveted treasures of old age: wisdom, knowledge, and balance of judgment.

He embraces, doesn’t shun, the complexities of the time, the different cultural sensitivities, and the need for a consensus with allies inside and outside the country. He is genuine in real and difficult times. The U.S. and the world now are not what they used to be 50 or 60 years ago; they are not what some literature drummed up to be at the end of the Cold War three decades ago. They are something complex that needs a new order, a new sense of direction, where a realistically hesitant sage can help to stir the country and the world, or thus Biden apparently claims.

Physically frail doesn’t mean mentally impaired. And the opposite can also be true — physically big doesn’t mean mentally strong. And in a President, the mind matters. Roosevelt led America through the New Deal, into the WW2 victory, and reshaped the world from the narrow confines of a wheelchair.

What kind of country do Americans want for themselves? A really or a fictionally strong one?

Trump and Biden seem to represent a competition between a glossy fiction and a harsh reality. Perhaps this is the American people’s choice in November of next year unless a third candidate tries to reconcile the stark differences.

In this contest, the dream has substance and dignity. It is the wish to improve the lives of millions left behind and without a voice. But this should not become a way to refuse reality.

Refusing reality

It is not just an American situation. In the world and Europe, many would like to refuse reality. Those predicting the early collapse of Ukraine sometimes wish to return to when there was no war. But as Gaza proved, war is spreading in space and time. In fact, there is no stopping it unless there is a miracle. An allied fleet could strike the Houthis in Yemen, and it might not just stop there. The world and the “West” (that now embraces large swaths of the East as well) must face reality to gear up for an ongoing war; only in this way can it hope to stop its spread or limit it realistically.

Philip Zelikow sums it up[1]:

The world has entered a period of high crisis. Wars rage in Europe and the Middle East, and the threat of war looms in East Asia. In Russia, China, and North Korea, the United States faces three hostile states with nuclear weapons and, in Iran, another on the verge of acquiring them. Beyond the headlines, states are failing in Africa, Latin America, and Southwest Asia, and enormous migrations are in motion. Having just weathered a pandemic that was the costliest crisis since 1945, the United States must now contend with other urgent transnational challenges, such as managing energy transition amid a deteriorating climate, the rapid development of artificial intelligence, and a global capitalist system under more pressure than it has been for decades. Unpacked, each one of these issues has its own set of complex problems that few understand. And on almost every issue, whether they like the Americans or resent them, people in the world look to the U.S. government for help, if only in organizing the work. The Americans cannot meet this demand. Their supply of effective policies is limited. The United States does not have the breadth and depth of competence—capabilities and know-how—in its contemporary government. The problem has existed for decades, as has been depressingly evident from time to time. What is new is the context.

Possibly, it is also because of politics and political challenges that had to be met in the past three decades, at the end of the Cold War but had been cavalierly ignored. The West followed a convenient fantasy of globalization – that the world was flat and that fair trade, fairly regulated by the newly formed WTO (World Trade Organization), could take care of everything.

But history would show that politics goes beyond trade. Ambitions and sentiments, whether personal, national, or religious, may not heed commercial self-interest. Wars that ultimately proved useless and disruptive in Afghanistan and Iraq started with too much ease and were supposed to crush the easy globalizing vision. The U.S. and the world conversely clung to it, driven by shallow business greed, and failed to prepare.

In contrast, other countries, who saw through the financial veneer of trade, saw the change and prepared for it. “The governments and media of China, Iran, and North Korea have been mobilizing for war. Russia is already at war and preparing for a long one… the fashion was to critique the United States’ hunger for empire, its endemic racism, its endless militarism, and its voracious capitalism. The implied corollary was that if the U.S. government were such a malign force in the world, then everyone would be better off if it stayed home,” Zelikov argues.

The practical result is the flopping statecraft in the U.S.

“The ‘how’ is the ‘craft’ in statecraft. Most of what the U.S. government does is distribute money and set rules. Relatively few parts of it mount policy operations, especially diplomatic ones. Doing so requires complex teamwork. Officials must master international choreographies, intricacies of law and practice, and a bewildering variety of instruments, cultures, and institutions spanning societies. The ability to do all that is a fading art in the United States and the rest of the free world. As it fades, hand-wringing and platitudes take its place. Officials paper over the gaps with meetings and pronouncements.”

To address it, the U.S. should undertake a massive “party building” effort of the kind the Chinese Communist Party has taken in the past decade. But this is apparently not happening. Conversely, the failings of the U.S.-led globalization and the domestic and international flops helped to change the perception of the U.S.

“All regarded the United States (or the United Kingdom in its day) as the anchor of a domineering imperial system that tried to block their own aspirations. They rallied other countries that also felt oppressed. But beyond that, the partnerships exhibited no common master plan. The partners rarely trusted one another. They often did not even like one another… What is different this time, compared with those past eras of confrontation, is that the American public has not absorbed the gravity of the dangers, and the country’s industrial base is much narrower and less agile. The United States relies too much on ill-focused military insurance policies and has not adequately prepared plausible operational strategies short of direct warfare.”

Zelikov points out that in 1941, the U.S., although not at war, prepared for war. Then the U.S. should do it now. But it is different at this moment. War started in Asia and Europe, in 1937 in China and 1936 in Spain. American volunteers fought in both on what was to be the “right side.” Plus, World War I had finished just in 1918, followed by a wave of revolutions in Europe, lasting almost a decade, and China had been constantly at war internally since the end of the Great War.

That is very different from the delusion of eternal peace stemming from the end of the Cold War and the onset of globalization.

This reveals the present American sense of detachment and the limited repertoire the U.S. is unfolding facing the crisis, as remarked by Zelikov. The result is the U.S., and the West are dragging their feet on clearly supporting Ukraine and governing Gaza simply because they are seen as two disjointed episodes and not as elements of one comprehensive challenge.

Ugly America

Plus, internally, the U.S. is not as attractive as it used to be. Seeing America from Beijing, Chinese people feel little sense of personal security. Parents sometimes hire security services to check in on and look after emergencies for their kids studying in America.

Here is a preliminary list of things that apparently do not work in America, seeing them from abroad:

- Drugs, too many opiates, problems with tolerating pain

- Too many guns

- Too much sugar and fat in the food

- Inadequate and deteriorating primary schooling

- Bad and deteriorating basic healthcare

- Decaying infrastructure

- Heartland-coasts divide

- Woke and anti-woke divide

These concerns ground more superficial worries about the challenges at hand, according to Zelikov:

Across the free world, the current period of crisis has spotlighted the mismatch between the institutions it had going in and the quality of effort it needs now. The public debates about national interests are largely disconnected from the practical issues. In the medium term, the U.S. government and its partners must examine whether their institutions—especially the civilian institutions that deal with finance, commerce, technology, and humanitarian relief—are really fit for purpose. People meet constantly, but they strain to get things done. At the end of 2023, the economic side of the U.S. government was taking protectionist actions that were sabotaging cooperation with allies on green technology, critical materials, and common management of the digital revolution at the same time that Biden claimed to be rallying the free world…

But the European experiment in common foreign policymaking has not been successful, and national governments must step up to their heightened responsibilities in this time of crisis. As for military power, the overreliance on small numbers of extremely expensive, exquisite American systems seems out of date and unaffordable, even for the United States. The Ukraine war has encouraged the Pentagon to make big bets—for example, instituting the Replicator Initiative, which is supposed to mass produce and field thousands of weapons that use emerging technologies…

The operational talent that Western policymakers displayed in the twentieth century was not in their genes. It was the accumulation of hard-earned experience and an accompanying culture that reinforced practical professionalism, including new and difficult habits of cooperation with international partners. There is only one way to recover these skills: practice them again.

There is an objective difference between the U.S., its allies, and its adversaries. The U.S. and its allies hold the world boat together as it is and must change it to adapt to present circumstances while sailing it. The adversaries just need to poke holes in it.

Moreover, the boat is diverse, made of very different pieces that are not well welded or glued together. It is vastly held by economy and trade, which have been globalized, i.e., it’s partly in the hands of the adversary.

The adversary boat is taking water, too. Still, being simpler and with fewer responsibilities makes it easier to keep afloat while the American ill-constructed boat may sink a piece at a time. Europe, for decades the mainstay of American politics during the Cold War and globalization, feels it is not aligned, and others are too.

Moreover, trade is a complex machine, not a one-way street. Adam Tooze noticed, “The mistake was not believing that economic interconnection produces real social, economic, and political change. It did. The mistake was to imagine that this transformation was a one-way process that would automatically secure order — and that order would be to the liking of the West. That was a simplistic lesson supposedly taught by the Cold War of the 1980s, which our experience in 2023 should finally have laid to rest.”[2]

In other words, more trade without a clearly shared political framework can create more instability and disruption.

U.S. and BRI

The adversaries also have positive alternatives to the America-led world. China has the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) set to redesign the globe around China’s economic, cultural, and political centrality. Russia offers its traditional values, which are also the pristine version of Western and American values. The two political offers are objectively at odds with one another but are driven together by their shared opposition to perceived weaknesses of the Western offers.

The U.S. needs something new and different; it can only be a global “road,” not necessarily an alternative or confrontational to China’s BRI but independent from it. The U.S. can do it with the Cotton Road, setting up a system of agreements that can also be used to develop Africa and the Americas. Here, there must be Asian and global allies.

The work on values is more complicated, and here, Pope Francis is blazing the way, opening the way to new sensibilities but holding the Church together, blessing same-sex couples but not marrying them, and having women become deacons but not priests. Pope Francis is keen on steering the Catholic traditions on a new path but without breaking with past sensitivities.

The United States could face similar challenges. Some in America might want to concentrate power in the name of greater efficiency. With this, we walk on very thin ice because America could give up the one thing that makes it special.

Freedom and democracy, and their advancement in the world, are the things that make the U.S. rise above its stations, the things that draw people from all over the world to America. Without it, there’s only national self-preservation expansion of one’s benefit. If that is so, why should one choose the U.S.? One would choose his own country over anyone else’s or the most populous country if he is genuinely selfless; yesterday, it was China; now, it would be India.

Any country holds its people together through a combination of freedom, economic benefits, and violence. Granting more freedom makes that state relatively more efficient because it can function with fewer economic benefits and violence. Less freedom changes the balance, and the state should spend more on benefits and violence, which are met with waste and opposition, starting a complicated vicious circle. Freedom is the one thing that makes the U.S. comparatively more efficient.

Its competitors or adversaries may claim that U.S. democracy is fake, but better fake democracy than no democracy at all. If America undermines its democracy, it weakens its special power worldwide and complicates its domestic order. Then, it’s only a brutal struggle of force, internally and externally, and the U.S. might not be the strongest for too long.

Here, a recent outstanding work has outlined U.S. priorities vis a vis China but in general with the world[3]:

U.S. strategy must be based on the four fundamental pillars of American power: the power of the nation’s military; the status of the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency and mainstay of the international financial system; global technological leadership, given that technology has become the major determinant of future national power; and the values of individual freedom, fairness, and the rule of law for which the nation continues to stand, despite its recent political divisions and difficulties.

Second, the U.S. strategy must begin by attending to domestic economic and institutional weaknesses…

Third, the United States’ China strategy must be anchored in both national values and national interests. This is what has long distinguished the nation from China in the eyes of the world. The defense of universal liberal values and the liberal international order, as well as the maintenance of U.S. global power…

Fourth, U.S. strategy must be fully coordinated with major allies so that action is taken in unity in response to China…

Fifth, the United States’ China strategy also must address the wider political and economic needs of its principal allies and partners…

Sixth, the United States must divide Russia from China…

Seventh, the central focus of an effective U.S. and allied China strategy must be directed at the internal fault lines of domestic Chinese politics in general and concerning Xi’s leadership in particular.

Eighth, the U.S. strategy must never forget the innately realist nature of the Chinese strategy that it is seeking to defeat. Chinese leaders respect strength and are contemptuous of weakness. They respect consistency and are contemptuous of vacillation. China does not believe in strategic vacuums.

Ninth, U.S. strategy must understand that China remains for the time being highly anxious about military conflict with the United States, but that this attitude will change as the military balance shifts over the next decade…

Tenth, for Xi, too, “it’s the economy, stupid”…

The list of core domestic tasks which the United States must address as part of any effective strategy for dealing with Xi’s China is familiar…They include, but are not be limited to, the following:

- reversing declining investments in critical national economic infrastructure

- reversing declining public investment in science

- ensuring the United States remains the global leader in the major categories of technological innovation including artificial intelligence (A.I.)

- developing a new political consensus on the future nature and scale of immigration to the United States in order to ensure that the U.S. population continues to grow…

- rectifying the long-term budgetary trajectory of the United States so that the national debt is ultimately kept within acceptable parameters…

- resolving or at least reducing the severe divisions now endemic in the political system, institutions, and culture…

- safe-guard, build, and even expand the liberal international order…”

Prima facie, the work is about China, the centerpiece of American and global concerns and challenges, but it is really about the new world order. The point is that there can be a balance point in the future to compromise the different worries peacefully. This is the real goal for a peaceful future.

[1] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/atrophy-american-statecraft-zelikow

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/c2b5ab2a-6634-4620-93f9-cec83170ce67

[3] The Longer Telegram: Toward A New American China Strategy.