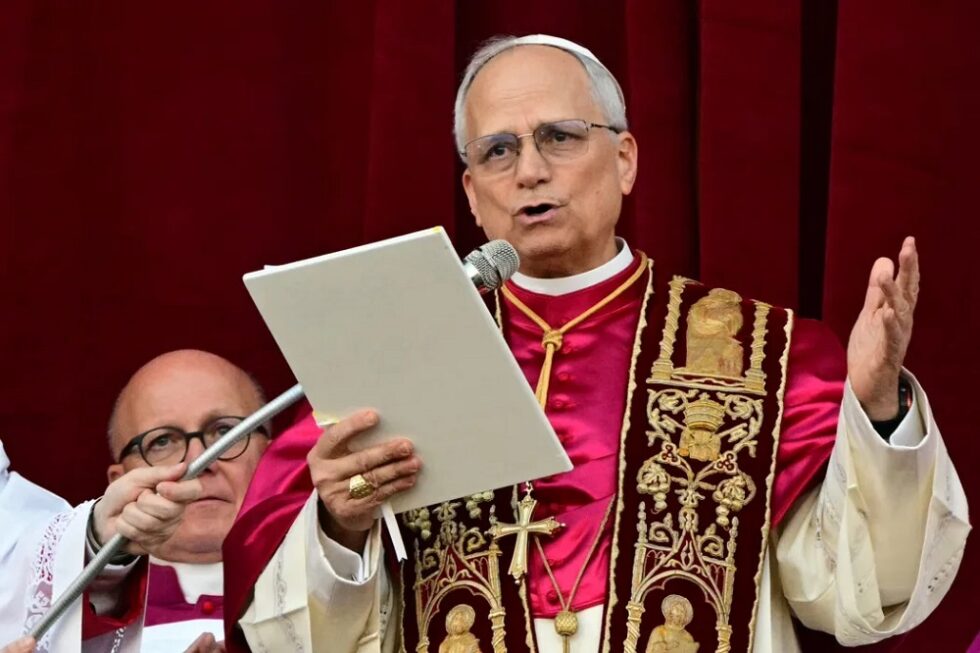

The election of Robert Francis Prevost as the new Pope, with the name of Leo XIV, went smoother than the confirmation of the German Chancellor Merz by the Bundestag. Just within three weeks after the death of the late Pope Francis the Catholic Church has regained its full governance. A sign of a system that works well, efficiently, and fast. Brother Leo was a companion of Francis of Assisi by the time the Friars’ Order was already an institution recognized by the Catholic Church. Choosing this name, Prevost has symbolically set the «spirit» of his ministry as Pope. His first words are programmatic: peace, bridges, synodality.

The First Vatican Council (1869-1870) was a crisis-management gathering. It was a Council summoned for dealing with the loss of the Pontifical State, on the one hand, and with the challenges set by modern reason to the Catholic faith, on the other hand. With the dogmatic constitution «Pastor aeternus» (18th July 1870), the Council declared the infallibility of the Pope in matters of faith and moral.

In this way, the Council ended up producing an image of the Catholic Church which led to believe that every question concerning the Petrine ministry had settled once and for ever. Due also to its sudden postponement on September 20th 1870, just ten days after the so called Breach of Porta Pia and Rome’s annexation to the Kingdom of Italy (9th September), the First Vatican Council reacted to the loss of the Pontifical State by isolating and immunizing the Pope from the life of the Catholic Church itself: making of the Petrine ministry a sort of hypostatized body removed from the vicissitudes of human history.

Yet such dogmatic statement about the Pope only find its meaning and intelligibility if read and understood within that same history, in relation to which the Catholic Church believed to have found the secret formula for a perfect separation.

Beyond Sovereignty

Having reached the end of the dialectic constitutive of European modernity, through which Church and State shaped themselves on each other, preventing each of them to totalize the space of human life, after losing the Pontifical State the Catholic Church countered the absolute sovereignty of the State making the body of the Supreme Pontiff the symbol of its own power of absolute sovereignty.

In this way, all the power of government, legislation, and judgment conflated into the person/body of the Pope – even if only within the religious/spiritual «territory» of the Church.

Such territory, however, was much larger than any state sovereignty, because it included the individual conscience of Catholic people wherever they were. From a geopolitical point of view, this Vatican counteract to the loss of the Pontifical State represents the end of the modern era at global level.

European states did not grasp the geopolitical consequences of this redefinition of sovereignty done by the Catholic Church, and they went on doing business as usual. It is at this point of history (1870), and not just at the turn of the 20th Century, that Europe and its politics started sleepwalking. Shortly thereafter, modernity as Europeanization of the world would be swept away by two devastating wars that had their epicenter at the very heart of Europe itself.

Within the Catholic Church the effects of this understanding of sovereignty lasted into the first decade of the 21st Century—making it a sort of archeological remnant of an era that had long gone. The resignation of Pope Benedict XVI represents the moment of Catholic awareness of the dysfunctionality (including for faith and moral) of this historical anachronism.

It is perhaps from this act of resignation that we must start to piece together a new vision of the Petrine ministry in the Catholic Church for the sake of the world. Pope Francis was able to speak effectively of a «change of era», with all this entails in the evangelical reconfiguration of the Church as institution, only because his predecessor had closed modern times for Catholicism by withdrawing his body from the seat of Peter.

The power of practices

Withdrawing a body, however ambiguous this gesture remained until the death of Benedict XVI, is certainly a juridical act; but, long before that, it is a practice charged with powerful symbolism. By exposing his body, Ratzinger sought during his lifetime to tame the symbolic significance of his gesture, but he was unable to control the disruptive force of the practical act of his corporeal withdrawal from the Petrine ministry.

And it is precisely the force of this practice, established by Benedict XVI, that represents the legitimacy of Pope Francis’ pontificate. This legitimacy, by virtue of its origin in Ratzinger’s decision, did not have to follow a line of continuity, as people were obsessed with trying to show (especially at the beginning of Francis’ pontificate), but required to go in the opposite direction: namely, discontinuity.

This turning point is decisive for the future mission of the Catholic Church and, at the same time, extremely fragile. It is fragile because its power to give back the Church as institution to the Gospel of the Kingdom is not a formal/legal act, but a practice—and it must remain so in order to be effective over time.

Unlike what was hoped for in Ut unum sint by John Paul II (1995), after Benedict XVI and Francis, the Petrine ministry in the Church in favor of the world and human history can only be reconfigured on the level of its actual practices—and not on that of theological theory or juridical accommodations.

The body of the pope can no longer be the symbol of a community closed in on itself, dominating the consciences of those who belong to it; but it must become the driving force of a welcoming expansion of the Catholic Church in which the distinction between us and them, inside and outside, is subjected to the harsh teaching that Jesus addresses to his apostles and disciples when they think to have exclusive rights over the Kingdom and its destination.

Synodality

The Catholic Church today is shaken by widespread resentment echoing the «feeling» of the older son, irritated by the superabundance of the undeserved that gestures of mercy and the hospitable openness of the Kingdom always bring with them. On this resentment, as old as the Gospel itself, a theory of division has been built over the last decade. Division that Pope Francis would have dramatically and recklessly produced in his Church. What this charge moved against Francis did not realize it is that when the Petrine ministry sticks to the Gospel, it is certainly on the side desired by God—however fallible this may appear in human eyes.

Synodality, as fundamental way of being of the Catholic Church, is precisely the practice that aims to free it from the traps of this resentment (which can sometimes affect some, sometimes others). Bringing the Church beyond the logic of «either me or him» but also beyond the absolute monarchical principle of Church government. Outside the former because that logic misses the clear imperative of the Gospel; outside the latter because it is historically dysfunctional to the mission of the Catholic Church within the history of men and women living concretely in the reality of our time.

The reform of the Vatican Curia has created the juridical conditions for a synodal governance of the institution «Church», but it cannot by itself produce the practices that will effectively implement it. Their invention and implementation is an urgent matter for the Catholic Church as institutional body—and as a global institution among other institutions in our contemporary world.

The body of the pope can no longer be the isolated and immune principle of total governance of the Catholic Church, but must increasingly take shape as a space of synodal synthesis where the administrative practices of the Vatican Curia and the cultural practices of the local Churches converge. Furthermore, as the Petrine ministry presides over both, it must guarantee respect for the evangelical precedence of the cultural commitment of Catholic faith, and therefore its pluralism, over the administrative power of the Curia.

The evangelical order

The restitution of the Catholic Church to the evangelical order, blocked for over a century because embroiled in the canonical order, is a long-term process that cannot be achieved by decree, but must be characterized by appropriate and corresponding practices. Pope Francis represented the dawn of this return of the Catholic Church to the destiny imagined by God for it in the present time. This also involves a change in the relationship with the truth and a reconfiguration of the symbolic body of the pope, who attests to the whole Church that it actually dwells within the realm of the truth of its mission for the sake of the world that we all inhabit.

In this sense, the truth is no more a matter of institutional and juridical exclusivism and becomes a matter of effective practices of alliance—in service to the world, in protection of the least and the excluded, in the name of the justice desired by the God of Jesus. Such justice is for everyone, for the orphan and the widow, for the prostitute and the tax collector, for the woman with the hemorrhage and the Syro-Phoenician woman, for Zacchaeus and the Canaanite woman—and not only for selected few.

Covenant means not being alone, but it also means recognizing a common destiny and a shared destination. It means building bridges, not impenetrable secure borders. Bridges between the different ways of being Catholic; between the cultural diversity of Christian communities rooted in their contexts of life; between religions; between peoples and nations. Alliance means making every human being feel that no one is excluded from God’s desire, that the joy of his intimacy is the common destination of all of us.

The restitution of the Catholic Church to the Gospel order requires an exercise of the Petrine ministry that protects and preserves in its practice the primacy of the word of God over the ecclesial institution and its juridical order. Only if the Catholic Church manages to hold fast to this critical difference between the Gospel and itself will it be able to become a constructive agency within the penultimate realities of the world to which it is destined.

Accepting as institution the risk of this return to the Gospel, safeguarded by the symbolism of the body of the Pope who makes alliances and intercedes for the world without distinction of belonging, means opening human history to the Kingdom of God and not expanding the sovereignty’s space of the Catholic Church.

Openings of the Kingdom

The alterity of the word of God and the opening of the Kingdom, firmly attested by the Petrine ministry within the Catholic Church for the sake of the world cherished by God, represents the strength that the Church needs to establish practices of dialogue between peoples and nations, together with synodal forms of negotiation between opposing parties—of which the nihilistic outcome of modern democracy, that today threatens the order of civil coexistence, urgently needs in order not to legitimize democratically new totalitarianisms as a form of the rule of law.

Restored to its evangelical meaning, the Petrine ministry will be able to become a practice that bounds together care for the Catholic faith and care for the destinies of the world. A practice on which political agencies could draw new strength and inspiration for honoring the shared dignity of every human being. A corporeal dignity to which the God of Jesus bound himself forever in the incarnation of his Son.