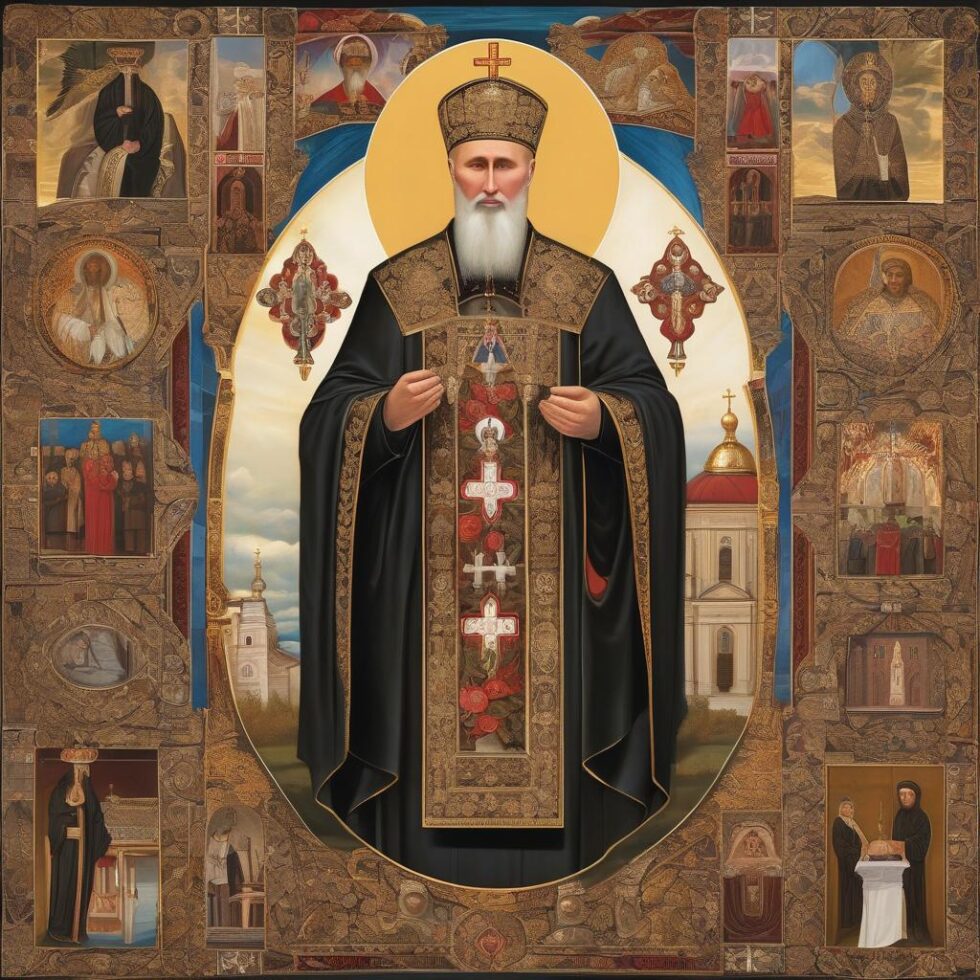

Religion as a political tool – The Russian Church is tying a knot with the Serbian Church to draw Belgrade closer to Moscow

There is a moment during the triumphant visit of Patriarch Porfirije of Belgrade to Moscow (April 21-26) where any openness toward the “social revolution” sparked by Serbian students on November 1, 2024—following the collapse of a railway station canopy in Novi Sad that killed 15 (later 16) people—seems to vanish (see https://www.settimananews.it/informazione-internazionale/serbia-crisi-politica-e-sociale/).

In the dialogue between Russian President Vladimir Putin, Patriarch Kirill, and Porfirije, the harmony and closeness of the two Churches transform into political alignment. The Serbian hierarch labels the extraordinary popular movement—which polls show enjoys 80% support—as a “color revolution.” This definition, already echoed by Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, is particularly alarming to Russian ears, especially after the Ukrainian case.

The conversation, published on official websites, begins with Putin praising the unity of the two Churches and peoples and confirming Vučić’s attendance at the celebration of the “Great War” victory (Porfirije assures that Vučić will be there “regardless of circumstances in Europe”). Putin also expresses support for the Sabor, the assembly of the “Serbian world,” which on June 8, 2024, gathered representatives from Serbia, the Republika Srpska in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and the Metohija region in Kosovo (see https://www.settimananews.it/chiesa/serbia-ortodossa-laicita-perduta/).

A “Colored Revolution” in Serbia

Porfirije responds by thanking Putin “for all he does in terms of values” and for the “loving and cooperative” relations between the two Churches. He quotes his predecessor Irinej: “Our small boat, sailing in stormy seas, must always stay close to the great Russian ship.”

“The Serbian people see the Russian people as one with us. Serbs often place more hope in Russian politics than in their own—a paradox, but true.” He also cites the current Patriarch of Jerusalem, Theophilos III, who considers Putin the “winning card” for Orthodoxy.

His greatest concern is Metohija, the Kosovo region home to key Serbian Orthodox sites. He acknowledges that China and Russia have so far prevented escalation: “We ask you to maintain this stance and do everything possible. Because, beyond politics, without Kosovo and the Republika Srpska, the Serbian people have no future.”

The fate of Kosovo, Republika Srpska, and Montenegro “depends on Russia’s global position. My hope—and that of most of our Church—is that in any future geopolitical division, we remain within the Russian sphere.”

Irinej of Bačka, seated beside the Patriarch, clarifies: “In the Russian world—the Russkiy Mir.”

“Yes, in the Russian world, the Orthodox world. We discussed Orthodoxy with His Holiness (Kirill). It’s not simple. Now we have a revolution—how to put it?”

“A colored revolution,” Irinej specifies. “A colored revolution, as you know. I hope we overcome this temptation. Western power centers don’t want to develop Serbian identity or culture.”

United Against the West

Both delegations were high-ranking. Alongside Patriarch Kirill was Metropolitan Anthony, the “number two” in charge of international relations, while Porfirije was accompanied by Bishop Irinej of Bačka, a key figure in the Serbian Synod, a staunch Russian supporter and seasoned polemicist. After meeting Kirill and Russian Church leaders, Porfirije held the aforementioned dialogue with Putin.

In the following days, Porfirije visited Serbian churches and institutions in Moscow, the Donskoy and Savvino-Storozhevsky monasteries, and the Trinity Lavra, receiving high ecclesiastical honors and an honorary doctorate from the Moscow Theological Academy. While theological collaboration was emphasized, the Serbian Church also stressed the need to protect monastic presence in Metohija.

The rhetoric was relentlessly anti-Western. Both Churches, having endured communist persecution, now agree, as Kirill stated, on “the pastoral mission for modern man. Though totalitarian persecutions have ended, the clash between Church and secular life remains dangerous. False ideals—material wealth and comfort—are promoted, while Christian moral values are marginalized. Thus, our Churches must unite in mission and theology […] Christianity is in conflict with modern Western culture, which has become fully secularized and atheistic.”

The Serbian Church is Russia’s closest Orthodox ally. Porfirije condemns contemporary ethics: “Non-spiritual, even anti-Gospel values are embraced. Some theological schools are influenced by global opinion and anti-Christian ideologies.”

Notably, neither side mentioned the three-year war in Ukraine—a raw nerve left untouched.

A Surprising Protest Movement

Beyond Moscow’s pomp, Serbia’s social and political tensions persist. The Novi Sad station collapse triggered a massive, peaceful, yet pervasive movement, exposing endemic corruption (a €1.9 million project ballooned to €435 million), murky administration (documents vanished post-tragedy), and political favoritism (contracts going to ruling party allies).

Students lead the protests. Within weeks, over half of Serbia’s universities were on strike, while high schoolers blocked bridges and roads in 15-minute silent demonstrations. Over 200 cities joined, with farmers, lawyers, professors, and unions supporting them. A general strike (March 7) succeeded, forcing the Novi Sad mayor and two ministers to resign, followed by PM Miloš Vučević on January 28.

The government responded with repression: police clashes, threats to professors and journalists, NGO expulsions, and school inspections. Pro-government rallies failed to counter the momentum. Protesters briefly occupied TV stations.

Vučić promised reforms but threatened to deploy special forces. Students sought international support, even biking to Brussels, but the EU hesitated to abandon Serbia’s government. U.S. envoy Richard Grenell stated: “We respect democratic processes but don’t support those undermining the rule of law.” The Serbian diaspora in Europe and the U.S. offered stronger backing.

The Church’s Ambiguous Stance

The Serbian Church has wavered but largely supports the government. A theology faculty that backed protests was pressured to retreat, as were some Metohija monasteries. Only Bishop Grigorije in Germany openly sided with students’ demands for democracy and transparency.

Porfirije called for mutual respect and an end to tensions. In January, he demanded accountability for attacks on protesters, but by March, the Synod urged “understanding and dialogue” without assigning blame. When protesters invoked Patriarch Pavle’s 1991 stand, the Church warned against “manipulating his memory,” insisting on neutrality: “The Church doesn’t take sides.”

Yet the Church’s support for the 2024 Sabor, nationalist historical narratives, and defense of Republika Srpska’s Milorad Dodik (condemned by Bosnia’s Supreme Court for violating Dayton) reveals its leanings.

The new government, presented on April 15, appears poised for repression. After his Moscow remarks, Patriarch Porfirije seems unlikely to be a safeguard for Serbia’s civil society.